Bobby Colomby and John Scheinfeld

Explain What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears

by Jay S. Jacobs

“What goes up, must come down.” That line is not just the opening salvo of 1960s and 1970s hitmakers Blood, Sweat and Tears’ classic smash hit single “Spinning Wheel,” but it also is sadly a pretty accurate description of the band’s career. However, it was more than just a spinning wheel that got to go ‘round which pulled the group down from the heights of stardom.

The story is much more complicated than that. It is a sordid tale of political intrigue, blackmail, communism, consumerism, Richard Nixon, hippies, immigration, oppression, fighting, Abbie Hoffman, extremism, the generation gap, Cold War posturing, dealing with The Man, far-right fanaticism and an early example of what would later come to be called “cancel culture.”

It is a story that has barely been told in the 50 years since the band’s glory days, but the whole amazing story is brought out into the light by documentarian John Scheinfeld in his latest film, What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears?

Scheinfeld has specialized in films which are pieces of musical excavation, taking deep dives into forgotten (or underexplored) pop music sagas such as The US vs. John Lennon, Chasing ‘Trane, Herb Alpert Is, and Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talking About Him?).

Helping Scheinfeld to dig up the truth was Blood, Sweat and Tears founder (and former drummer) Bobby Colomby. While Colomby is no longer anchoring the backbeat on the skins for the current incarnation of the band, he still is in charge of the group as well as working as a producer.

Colomby put the band together in Greenwich Village about the time of the summer of Love. Their first album – Child Is the Father of Man – had lead vocals by Al Kooper. The record was well-respected but did not do particularly well or spawn any hit singles. Colomby felt that Kooper, while a brilliant instrumentalist and producer, was not really a good enough singer to lead the band. When he broached the subject to Kooper, he quit rather than give up vocals.

He was replaced by Canadian singer David Clayton-Thomas, who helmed the band’s self-titled second album, which exploded Blood, Sweat and Tears onto the radio and the record charts. That album spawned three huge hit singles – a cover of an obscure Brenda Holloway single “You Make Me So Very Happy,” signer Clayton-Thomas’ composition “Spinning Wheel” and a cover of Laura Nyro’s “And When I Die.” Interestingly, all three singles peaked at #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, being held out of the top spot by such classics as The Fifth Dimension’s “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In,” Zager & Evans’ “In the Year 2525” and The Beatles’ “Something” and “Come Together.” (The Beatles songs were a two-sided single.)

However, their time at the very top of the charts pretty much came to an end after a disastrous tour of Communist Bloc countries which was set up “as a diplomatic exchange” by the US State Department. What was never told is that the band was strong-armed into doing those shows by the government, which was threatening to deport lead singer Clayton-Thomas, a Canadian citizen.

Therefore this stridently non-political (though most of the members tended to be left leaning) group of musicians became pawns in a political game that they really had no interest in playing. They were vilified by both the left and the right.

The band has continued on over the years with multiple line up changes, because like the song says, “And when I die and when I'm gone, there'll be one child born in this world to carry on, carry on.” However, while they had some periodic hits after the infamous Iron Curtain tour – like “Hi-De-Ho” and “Lucretia McEvil” – the band never again reached the rarified air of the eponymous album’s pop culture dominance.

Blood, Sweat and Tears are much too innovative and talented a band to be confined to the dustbin of history. Hopefully What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears? will help to return the spotlight to a woefully undervalued body of work and an envelope-pushing musical act. That would make us so very happy.

Soon after the release of the film, we chatted on Zoom with Colomby and Scheinfeld to get the true story of What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears?

The story that this film exposes what led to the downfall of Blood, Sweat and Tears has been pretty unknown for all these decades. John, how did you find out about what happened and decide it would make a good film?

John Scheinfeld: It’s all Bobby Colomby’s fault. We met a few years ago. He had seen my Chasing ‘Trane film and wanted to meet, so we had lunch. That was about six years ago and that was that. Then about two months before COVID hit, he called out of the blue. He said, “I’ve got a story I want to tell you, let’s go to lunch.”

Bobby Colomby: I said COVID is coming! (laughs) No, I didn’t.

Why did you think it was time to get this story out?

Bobby Colomby: I didn’t think that. I hadn't thought about it, honestly. But 50 years, life goes on you. You're in the present. You're thinking of what you're going to do tomorrow, not harping on yesterday. I was pretty much not thinking about it until my friend Rupert Perry, who was an executive at EMI for years, and a wonderful man. I was having dinner with him. He used to play drums. He said, “Why did you stop playing?” He just goes through my history, you know? I just said, “Well, on top of everything else, I kept the band together. I kept changing people. We had this eastern European [tour]…” I just mentioned it. Then I said, “Yeah, there was actually a film crew. [An] independent company heard about it, and they wanted to join us and State Department.” He's going what? He's flipping out. I'm not even that excited, but [Rupert] is flipping out. He has a friend that ran Thorn-EMI films. He said, “Find this film, because it exists somewhere.” I said, “Well, the company was called National General. Then I think they sold it to Filmways. I don't know. His friend goes to Paramount and goes to Warner Brothers and can't find anything. There was no mention of it at all. So that was the end of it.

But eventually you thought of contacting John about the story?

Bobby Colomby: Then I see Chasing ‘Trane. I'm a jazz fan. I was wondering how are you going to do anything on Coltrane? He's mysterious. The guy didn't do a whole lot of interviews, There’s not a lot of footage of him other than with Miles [Davis]. I'm thinking, “Boy, that'll be interesting to see how he does this.“ Then we end up having lunch. I'm just talking to him about stuff. I was just reminded, “Oh, that's right. You make films. Well, speaking of films…” I was just reenergized over the concept by my friend Rupert, and I brought it up.

John Scheinfeld: We went to lunch, and I told him how much I loved the band. I literally said, “What the hell happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears? Here you guys were, one of the hottest bands going, and then you weren’t. What happened?” He said, “That’s the story I’m going to tell you.” And that’s the story we told in the film.

Bobby Colomby: He said, “I was really a fan of Blood, Sweat and Tears. What the hell happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears?” I start explaining the story again. Then when I said, “And there is film somewhere on it,” his hair caught fire. [He said,] “I got to find this.”

John Scheinfeld: I saw in this, Jay, elements of a multi-layered story that really is more of a political thriller than it is a music documentary. We have elements of espionage. We have Vietnam. We have Nixon and Kissinger in the White House. We have film smuggling. We secret police in three communist countries. And I think at the heart of it, what really interested me the most was I felt there were some Shakespearean overtones here. A group of nine innocent guys who did something they had to do to save themselves, but in doing that they killed themselves. That to me is a fascinating story.

Blood Sweat and Tears were so unique musically, even for back then. What is it about their sound that you feel really made them stand out?

Bobby Colomby: First of all, the actual configuration of the band is the four horns. And they're not used in unison. They're not all playing the same notes, which a lot of bands do. In a lot of R&B music, when they had horns, they were almost like another rhythm guitar. (hums the sound). That kind of thing. (continues humming) That’s what they would do.

John Scheinfeld: I think what made Blood, Sweat and Tears so unique was the innovative sound that they created. They brought in elements of jazz. They brought in elements of rock. They brought in elements of blues. They brought in elements of classical. The combination of that at that time was very unique. I think that’s what accounts for the fact that the second album they put out, which is the first one with David Clayton-Thomas as the lead singer, at that time and for some years, was one of the biggest selling albums ever. They had three top ten singles off of that. They really influenced a lot of other bands, like Chicago, and Ides of March, and some of the others. But I think it was that sound that made them so unusual and really made them stand out.

Bobby Colomby: I'm a jazz fan. I have two older brothers. One was 16 years older; one was 17 years older than me. The oldest was a trumpet player, self-taught. Really good jazz player, who was really good friends with Miles Davis. My other brother managed Thelonious Monk for 14 years. So, I had Bach and Beethoven in my living room growing up. The only music I ever heard was jazz. I could never understand why everyone wasn't loving jazz, (laughs) because it was such a unique style of musical expression, smart and spontaneous. For me, it was exciting. Pop music was just not all that inventive. You knew what the next chord was going to be. It was rarely a surprise. Then there were lyrics that were not Johnny Mandel.

So how did the band come together?

Bobby Colomby: I started hanging around in the West Village. I was going to graduate school down there. I met Steve Katz, funny, nice guy. He was in a band that was about to break up [The Blues Project]. He and Al Kooper were in the band together and they couldn't stand each other. Al left first and then Steve left. I was hanging around playing in the village. I'm a self-taught drummer that never really fell in love with my drumming. I just thought I could do it, because if you played jazz, you got to be able to play. (laughs) I'm not comparing myself to Shakespeare in any way, but he really had a grasp of the English language. You have to have some understanding and some technique to play drums in the jazz idiom. Al Kooper heard me play and asked if I would join him for a fundraiser… for him. He wanted to leave America. He wanted to be a producer in England. He didn't have the money. He said, “Would you do this with me?” I said, “Why don’t you get Steve to play it?” “He won't do it. I hate him.” I said, “Don't be an idiot. Let me ask him.” I asked Steve. “Oh, he'll never want [me].” I said just do it. Play as a quartet. We played over the weekend at the Cafe Au Go-Go on Bleecker Street. He didn't raise any money.

Oh well….

Bobby Colomby: I was pursuing the concept of a band that would have jazz players, who were most of my friends, musicians who could play jazz. And some of the pop guys because they're my friends. We wanted to put them all in a room and see what happens. I said to Steve, “Why don't you call Al and see if we can have some of those songs that we played with him?” Because I liked them. That would be a good start for the band that I was going to put together with Steve. Steve called Al. Then Steve called me back and said, “Oh, good news.” I said, great. Al said we can have the songs. Fantastic. I'm ready to hang up the phone. “Wait, he wants to be in the band.” Uh oh. “And he wants to be the singer.” Uh oh. The uh oh was mistimed because Al is brilliant as a hustler. He knows how to get things done. He always has a big picture. He got us a record deal. I never would have done that in a million years. He gets us a record deal.

Wow.

Bobby Colomby: Then he kind of takes over the band. He's the band leader. He's doing everything. I was a little hesitant because I didn't think his singing was great. Especially in that world, if you want to be on the radio, which is how you had success, I didn't think his voice would really translate to the radio. Plus, he was a little bit on the fragile side. I watched a great producer, John Simon, on the first album, he had to get the punch in on the syllable sometimes to get him to sing so it was actually recordable. I saw that, I don't know how we're going to do this. Then I find out that he does a song, and he doesn't even include the rest of the band, just a string quartet. I'm starting to realize he's not a band member, this is a springboard for him. No problem because he's already got us a record deal and things are going. Then I called a meeting with Steve of the band and just said, “Al we have to get a singer. I'm not going to kick you out of the band, but we have to get a singer.” He said, “I'm the singer or I leave.” They voted him out.

Once David Clayton-Thomas came, you guys suddenly are all over the radio with things like “Spinning Wheel,” “You Make Me So Very Happy” and “And When I Die.” What was it like to be part of the band at that point when everything was just blowing up?

Bobby Colomby: That's a great question, because the answer is not what you think it's going to be. You don't know it. You don't know you're successful. You really don't have any idea what's going on. You're in the center of a hurricane and it's very still, everything else is going on, but you're just doing your thing. At this point, I'm the bandleader, so I have to organize a lot of stuff. I'm working with Clive Davis, who was wonderful to us. He believed in us. He believed in Al, also. He hired Al as an A&R guy. He kept us afloat.

John Scheinfeld: The interesting thing is there were nine guys in that version of the band. They stayed together from mid-1968 until late-1971. I think the success they had was a great surprise to them. I think they never thought they were going to be a major hit band.

Bobby Colomby: Once we heard David, at an audition, it was pretty obvious that you aren’t going to find a lot of voices like that. [David] was a band member. He was the hardest working guy. He was so professional. It was actually a pleasure because he knew this was his shot. He wasn't going to jump ship the second we had success. He was a lot of fun, except he's Canadian. Nothing wrong with being Canadian, most of the Canadians I know are wonderful people, certainly. Except someone from the government at that time [started keeping an eye on him.]

John Scheinfeld: Steve Katz tells a great story in the film about how he was looking at the charts one day and the self-titled album ended up and number 16. He thought, “Wow, this is great. We’ve got a hit record.” Then he called back into the woman that he knew there the next week and said, “So, where are we this week?” She said, “Well, I can’t find you.” He was, well, all right, we made it to 16. That’s pretty good. Then she called him back and said, “I didn’t think to look at number one.” (laughs) So I think to all of them, the success was a surprise, but a welcome surprise.

Blood Sweat and Tears had an awful lot of players in a single band, Obviously you couldn’t speak to everyone, but you got to speak to a good number of the guys who were in the band.

John Scheinfeld: We were able to talk to five of the band members. Two had passed away in the last five or six years. Two felt they really didn’t have enough to say, so that’s why we didn’t talk to them. But the five that we did talk to are David Clayton-Thomas, Steve Katz, Bobby Colomby, Jim Fielder and Freddie Lipsius, all of whom had very unique perspectives and very unique ways of speaking. You love that as a filmmaker because it really keeps things very fresh and alive when you’re watching the film.

As has been mentioned, most people don’t know the whole Iron Curtain tour story. Obviously, I don’t want you to tell everything, but could you just tease a little of the story for us?

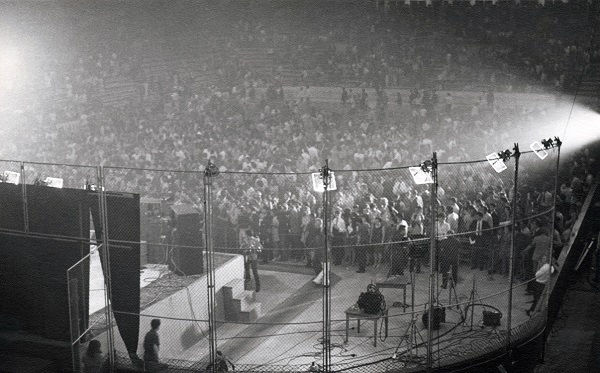

John Scheinfeld: Absolutely. In 1970, Blood, Sweat and Tears became the first American rock band to perform behind the Iron Curtain. The Iron Curtain, for some of your younger readers, was in the days when there was a Cold War going on between Russia and the United States. There was a demarcation line in Europe. If you were to the East of that, you were communist and under the sway of Russia. If you were on the other side of that, you were free and democratic.

Bobby Colomby: This is 1969-1970. This is when there's a war raging in Vietnam. There's a Nixon administration, which is dodgy at best. If you were under 30, most kids were against the war. Against Nixon. As we were. Not as a group. It wasn't anything we planned. But if someone put a mic on their chin and said, “What do you think?” we're all going to feel the same way. Steve was a little more outspoken. For him was like an outfit. “This looks good on me. I think I'm going to be radical.” He didn't go out and march. He didn't do anything extraordinary, but he believed, and he was more outspoken about it than anyone else. But we all had the same exact sentiment.

John Scheinfeld: Very few Americans had gone behind the Iron Curtain, much less a rock band. So this was, on one hand, a very exciting opportunity for Blood, Sweat and Tears. Why they did it is part of the mystery that we had to solve in this film.

Bobby Colomby: I guess a right winger, some senator, someone investigated David, the Canadian. Like “who the hell is this guy think he is telling us what to do in Vietnam?” Or “who does he think he is? He's against our President.” They found he had a jail record in Canada. And a green card… you have to have this green card today. It still exists. If you want to play in the United States and you're an alien, that's how you do it. You have to be certified or whatever. They revoked his green card. So we have the number one album, but we can't play in the United States anymore.

John Scheinfeld: There were elements of blackmail involved, pressure and government policy, and a number of other things that we detail in the film. They had to do this tour. It was not by choice.

Bobby Colomby: We had hired a manager. He was a devious guy. Either the State Department went to him, or he went to the State Department – which is a little left of Nixon, by the way. They weren't all in on him. They said, “Well, if you if you're having a problem with a green card, I think we know how to get it back. We're trying to get a relationship with some of the satellite countries behind the iron curtain that were controlled by Russia.” At the time the USSR.

John Scheinfeld: They went to three communist countries, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Poland. They did a number of concerts over a three-week period in cities within those countries. It's hard for us today, Jay, to understand just what life was like in those countries and what they encountered when they went there. Today, there are people who praise Putin and like the way he does things. What our band members found is that it is no picnic living under a dictator. It is no picnic living in a repressive society, where you can't say what you want to say. You can't read what you want to read. You're under surveillance. They can lock you up for no reason whatsoever. That's what they were walking into. It was a real eye-opening experience for them.

Bobby Colomby: To various degrees, each one of these countries that we had visited – Yugoslavia, Romania and Poland – had different levels of pressure from Russia. The worst was obviously Romania. When you see the movie, you'll see. It was an amazing thing. We knew that we had no choice. We knew we had to do this tour, or we were going to lose our singer right in the middle of our success. So, we did it.

John Scheinfeld: Each of the three countries had their own particular form of communism, so the experience in each of those countries was a little different. We talked about that in the film. Where they really had some issues was in Romania, which was the most repressive of the three countries. There was a near riot at one of their concerts. We talked about what happened there and the consequences of that riot.

Bobby Colomby: Obviously [we] couldn't announce it, couldn't tell anyone. But when the marquee says US State Department sponsored tour, that means the Abbie Hoffmans of the world who make their money and their fame by being extremists on the left side, they went, “Perfect. Let's go after the number one band and call them pigs and traitors.” That's what they did. We were squeezed from both ends. The right and the left just killed us. And we couldn't say anything.

John Scheinfeld: The real issue was when they came home. We detail that in the film, that they found themselves in the crosshairs of a polarized America. The country at that time was just as divided as we are now. The specifics were a little different, but left and right, red and blue, all of that existed then. They found themselves squeezed by both sides, which is what made their situation so unusual. Today, you're either criticized from the left or the right. They were criticized and hammered by both, and it really affected their entire career trajectory.

Bobby Colomby: Imagine you're about to get on a plane. If someone says to you, “so what do you think about your country, the United States?” You say, “We got to get out of the swamp Vietnam.” “Nixon should get out of office. He's untrustworthy.” Etc., etc.” You'd have all these things, right? Then you go over there, and you're up against communism. You see it face to face. Your reaction almost immediately is this is not a solution. This is not going to work. So the Abbie Hoffmans and the extreme leftists are out of their mind. They have no idea. Abbie Hoffman never actually picketed in Romania, never went to these places. (laughs)

John Scheinfeld: You know what it is, Jay – and you see it, because you cover so much pop culture. Movies, TV shows, music, books, whatever it is – they have a moment. That moment is where everything is just working great. You get great reviews. You're in demand for this. People want to see this. Everybody's talking about you. Everybody thinks you're great. That's where Blood, Sweat and Tears were. They were being elevated and they're famous and all of that. But as you know, just one little thing can throw that moment off. What happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears when they came back from this tour, it wasn't a little thing. It was a big thing. And the moment was gone. They continued to record. They continued to perform. But things weren't the same.

Bobby Colomby: I had a call from a woman from The New York Post. I used to love The Post. I used to read it on the subway. It was easy to read, great sports section. In the afternoon, it had the latest. I enjoyed the post. I was excited, because she called me at home after our tour and said, “Hey, I want to talk about the tour.” Oh, great. I said, “Do you have any kind of a travel budget? Because if you do, going there's really cheap. It is not expensive at all. If you go and come back, we can have a comprehensive interview because then you'll see what I saw.” She goes, “That's a great idea. Thank you.” Hangs up. Next day, there's a complete article in The Post about an interview she did with me that never happened.

It is pointed out in the film that despite being in the middle of the 1960s and early 1970s, Blood Sweat and Tears were not an overly political band.

Bobby Colomby: Not at all.

Steve was sort of political in the film. You said certain things that were a little political, but that might have been in hindsight. Mostly you guys were left leaning, but you're a musician, so you didn't really care about that stuff.

Bobby Colomby: You summed it up. That's exactly right.

Do you think that had the band known more about politics it could have missed some of the problems? Or do you think that the band were just sort of in the middle of a no-win thing?

John Scheinfeld: It's easy to look back at 1970 and what they encountered and do so through the prism of 2023, where PR people are everywhere. There's spin. There's spending. People are careful about what they say and all of that. That wasn't around in 1970. These guys were – and I admire them for it – they were all under 30. Like most young people at that time, they were against the Vietnam War. They were against what Nixon was doing with regard to the war and some other things. They weren't terribly out of step.

Bobby Colomby: The thing that has to be clear, if someone has said to us, “we got to talk to you, if you do this, it could screw up your career. Anyone over 30 will turn on you, because you know, because you're coming back and you're saying that you know communism is bad. How dare you say communism is bad. Nixon is terrible, you know?” If we knew all this, and someone said, “if you go on this tour, you're going to get slammed.” Or you lose your lead singer. (laughs) That's what people keep missing. Or you lose your lead singer. We're not about to lose our lead singer. So if this is the option, we have to take it. We can't announce it. The State Department made it a rallying cry. It got out of hand. It should have been a very quiet tour and we came back. That was the end of it, you know? Then he gets his green card back.

John Scheinfeld: It's this political rat's nest – as David Clayton-Thomas called it – that they ran into. I have to admire that they were just honest and candid and direct about what they saw over in those communist countries. And they got nailed for it. It was the media and the establishment that are really to blame here, not the fact that they should have done this, or they should have handled it this way.

Things, if possible, are even more polarized now than they were then. For example, watching that you were seeing echoes of the whole thing going on with Putin now and the Ukraine…

Bobby Colomby: Exactly the same. The only difference is today, there is extreme polarization, but it's horizontal. The right going to extremes and the left going to extremes. Back then was vertical. Over 30, under 30. That's the way it shook out back then.

John Scheinfeld: There are a lot of parallels that will resonate with people today. The obvious ones are the divide between left and right, red and blue, east and west. But also, I think the consequences of cancel culture. They didn't have a term for it back in 1970, but Blood, Sweat and Tears was an early victim of that. To look at that and say that's wrong, that is just wrong. When we were in editing, our historian Tim Naftali – who's one of the two CNN presidential historians, so he knows a lot – he was really talking about various aspects of this story and putting a lot of historical events in perspective. He did talk a little bit about how, when the government of Czechoslovakia tried to become more free and more democratic, the Russians couldn't handle that. So they rolled in and invaded with their tanks and forcefully put people back under the repression of the government. We couldn't help but think of Russian tanks rolling into Ukraine when we saw that footage.

What do you think the story can tell the current generation? Sort of as a cautionary tale?

Bobby Colomby: Yeah, that's exactly it. You answered your own question. It's a cautionary tale.

John Scheinfeld: History repeats itself. What's the old saying? If you don't learn from the lessons of history, you're doomed to repeat them. I think audiences today can learn a lot from what happened to Blood, Sweat, and Tears.

Bobby Colomby: This film is hardly a documentary of a band. It's not a music documentary. It's a moment in time for the band. It's a political thriller. It's a feature film. It's non-fiction, and the actors happen to be the participants.

John Scheinfeld: This is a cracking good story. It's like a great spy story that you could find in a spy novel or a spy film. I think people who are going to come to see our film will be really entertained. There's a lot of twists and turns in it, and a lot of fascinating voices in it. What we've really heard from a lot of people along the way – we've been in theaters since the end of March – it is the kind of film that stays with you. You talk about it. You talk about it with your friends as to what you saw. Some people have said, I got to come back and see it again, because there's so much stuff of interest in it.

There was 65 hours’ worth of film done on the tour. Basically, no one knows where anything is other than about an hour’s worth of footage, what was used in this film. Do you think the rest of it is in some giant government warehouse, like at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark? Do you think it will show up or do you think it's lost for good?

John Scheinfeld: Well, you've identified two of my nightmares, Jay. Again, for your readers, Blood, Sweat and Tears took a documentary film crew along with them before this Iron Curtain tour. It was an independent production company that was hired. They shot 65 hours of material. They recorded all of their concerts on eight-track. Not the eight-tracks that people had in their cars, but eight-track studio machines. They came back to LA with the idea of making a documentary for theaters because Blood, Sweat and Tears was that big. That's when more problems started with this footage.

Bobby Colomby: He got very lucky. He found a guy named Donn Cambern. I remember him from the tour. He was the director of that independent film that was being shot of our tour. He just wanted to shoot a full-length feature of a famous band playing in some interesting places. We also played in Western Europe on that same tour, but the crew was really there to follow us through Eastern Europe, because it was unprecedented at the time that an American pop band would be playing there.

John Scheinfeld: What we learned was that the State Department had seen a rough cut of a two-and-a-half-hour version of this film. They had problems with it. We detail what those problems were. Ultimately, the State Department had the final say as to what this film was going to be, and this film never came out. The production company went bankrupt at the end of 1970. The post-production house that physically had all the materials where they were doing all the editing, went bankrupt in 1971.

Bobby Colomby: John found Donn. Donn is one of the nicest men, I remember. He still was. He was already 90 years old [when the documentary was made], and it was [during] COVID, so it was hard to get him. Finally when it lifted enough so he could leave his facility, he came. I think his interviews were the most important in this entire film.

John Scheinfeld: So here we are 50-some years later, trying to pick up a cold case of where this stuff is. We check every independent film storage facility here in LA and in New York. We checked government facilities. There was no paper trail on any of this. What we've had to do is piece together, from what the band members remembered, what people on the tour remembered, and then we found we were able to get access to declassified State Department documents. We talk about in the film what we think happened to it.

Yes, that is covered.

John Scheinfeld: But to answer your question, my two nightmares are: 1) yes, the government put it in the Raiders of the Lost Ark warehouse. It will never ever be seen again. Or 2) I'm going to be out on the road – where I have been for the last couple of weeks promoting the film and doing Q&A's after some of the screenings – and somebody's going to come up to me after one of these Q&A's and say, “Why didn't you call me? I have it all in my garage.” (laughs) But I honestly think it's gone. What we did find was a pristine print of a cut that they did for TV. That was only an hour. That didn't get aired either. It was just sitting in this vault since 1971.

What was surprising is even for the stuff that was going to be in the TV documentary, they did show a lot of things. Although the State Department wanted to keep everything upbeat, it did show a lot of the oppression behind the Iron Curtain. Were you surprised to find that that was still in there?

John Scheinfeld: I was delighted that it was in there because it enabled us to properly tell the story. In those 60 minutes, we found almost everything we needed to tell the story, although we would have liked more, of course. But I think the answer is I wasn't really surprised that it was in there, because this thing never got released. I think because that stuff was in there, finally the State Department just said no, we can't put this out, no matter how you cut it.

The music sounded great, too, which is a little bit surprising, just because it's that old, and the footage had disappeared for a long time. Were you surprised by the quality of the music? You guys are releasing a soundtrack album with music from the tour. Were you involved in that, or is that something that Bobby handled himself?

John Scheinfeld: I was involved in some aspects of it. One of the things Jay that I like most about my job is the detective work. We find stuff. (laughs) Like we found that one hour of the film, we were looking for the recordings made during those Iron Curtain concerts. Their record label Columbia Records – which is now Sony Music – didn't have them. They weren't involved with this tour. I mean, we tried it, but I didn't think they really would have that stuff. Band members didn't have it, didn't know where it was. We tracked down engineers who were recording that stuff. They didn't know where it was. It all had been delivered to the documentary production company.

Bobby Colomby: When you deal with anyone that's had a history of making documentary films, they're better than detectives. They find stuff, man. It's really pretty amazing. Certain laws have changed, like the Freedom of Information Act and things like that. You're actually able to go in and get a lot of what was once top-secret information or confidential. Now you can get it. He's relentless. His team is relentless. They found tons. He found something in my house I didn't know I had, climbing up the ladder and finding tapes. He said, “What is this?” I said, “I have no idea.” It was actually the audio of the press conference after we came back from Eastern Europe.

John Scheinfeld: I had this researcher, Kathleen, who's very sweet and extremely persistent. She tracked down the family of the associate producer of the film crew for the documentary that never got made. He had died in 2018, but he had a storage unit. The family donated the contents of the storage unit to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences here in Los Angeles. They sat there for three years. Nobody inventoried the collection. Nobody knew what was there. This was just sitting on a couple of shelves somewhere. So Kathleen kept being very persistent. And finally a wonderful archivist named Warren went down there. Lo and behold, there were five of these eight track recordings made of those concerts.

I was surprised at how good the band performances from the tour sounded, because those tapes had been lost for a long time.

Bobby Colomby: Jay, my victory in this project, ultimately, hopefully, will be people that will say that was a great band. It was no secret why they were successful. They didn't sneak into a number one spot. I think we affected music generally. So many musicians have told me over the course of my career how much that meant to them, and how they learned their instrument when they heard what we did. I'm a fan of an arranger/composer named Vince Mendoza. I think he's brilliant. He's a contemporary, and he's just unbelievably talented. He told me the other day, by accident, he said, “Well, I learned a lot. Because in high school I had to write the horn parts out to ‘Lucretia McEvil,’” which is one of our songs. Then he picked up the trumpet and he just wanted to play like Lewis Soloff, our trumpet player, and his solo on “Lucretia McEvil.” That's how he learned to play trumpet. This is my favorite arranger/composer. He learned because of my band. That's quite something, actually.

John Scheinfeld: Across those five [tapes] were all but two songs that they performed on the tour. Why this guy kept those five, I don't know. We got [shows] 3,4,7,9 and 18. At one time, there were 18 of them. Why he didn't save all 18, or what happened to the other ones, we don't know. But we had them transferred to digital. Then we went into Capitol Records, the studio where Frank Sinatra and a lot of other famous artists have recorded. Bobby and this wonderful engineer, Allen Sides, took the original eight-tracks and mixed them. It really sounds like they were recorded yesterday. They were so clear and sharp. The band was so good. Some of the band members have said to me that BS&T was better live than on record. They were really good on record, so that should tell you something. They were just at the height of their powers here. These performances just will blast you out of your seat, they're so good.

Well, what was it like putting together the soundtrack album? I know that John told me that you guys had tapes of five of the 18 shows.

Bobby Colomby: Mainly, I would say 90% was one concert. That was in Poland. In the movie, David correctly remembers that was a moment in time that the audience was amazing. The venue was fantastic. The sound was great. We hit the stage and for us, it was like a huge exhale. After having been in Romania – again, see the movie, you'll see what happened. We played our asses off in that concert. There's no overdubbing. There's no fixing of anything. I mean, that was the concert. We just mixed it into stereo and 5.1 for the film or DVD.

What was it like hearing what you played again after fifty years of these tapes being lost?

Bobby Colomby: This is sort of a confession. I have said this before. It's not humble brag, I really wasn't a big fan of my drumming. I think if you go to any musician and say you're really great, they're going to tell you who their influences are, who their idols are, and say, “Well, if you, you know, if you want to hear great, you should check them out.” If you go to Eric Clapton, he'll tell you the greatest in the world, “Try Albert King, if you have a minute.” I was just not a big fan of my drumming. While I'm mixing, I get this out-of-body experience that I'm starting to feel like I'm a surgeon. While I'm at the control board and I'm doing the mixing with Allen Sides, I'm really an engineer. We're friends. We've done a lot of stuff together. We're just sitting there doing stuff. All of a sudden, I feel like a surgeon, and like another doctor in the middle of the surgery taps me on the shoulder and says, “Hey, Doc, by the way, that patient, this is you 50 years ago.’ I'm realizing I'm actually doing something that's neat. Play. 50 years ago. I hadn't thought of it. I haven't played since 1975, or something. It was the first time I liked my drumming. I would go and hear that kid. He's good.

What was it like just seeing yourself 50 years ago, and the old the old film footage?

Bobby Colomby: I don't obsess about, as they say, my own stuff. There's so much to do moving forward that involves other people that are wonderful musicians that I can help. That's really my emphasis.

John, you mentioned one of the great things about your job is you're able to do detective work. You've done a lot of really very terrific musicians over the years. Of course, Coltrane and John Lennon and Herb Alpert. My particular favorite of your subjects is Harry Nilsson. I wrote books about Tom Waits and Tori Amos like 15-20 years ago, and at that time – before you did your documentary – I was trying to convince my agent that I should do a book on Harry Nilsson. He said, “I don’t think that enough people know about him to make it worthwhile.” I was going, yeah, but he's got such a fascinating story. But, anyway, how do you decide who you’re going to cover? What do you look for in a musician’s story that makes you want to bring it to the screen?

John Scheinfeld: Great question. It's really two things. The first one is: What is the story? Is it just this happened, this happened, this happened, this happened, this happened, and you're tracking a career? That's one kind of a story, and I've done a few like that. But I'm much more interested in a story that has a lot of layers to it, and a lot of different directions to it. That will take you off on the side trips of really fascinating things. Because these lead characters are so fascinating, complicated, and complex. Harry is one of the most complicated, complex musicians you possibly could have. Sweet, gentle, talented, and totally crazy and self-destructive. I'm looking for those layers that make a story worthy of being up on a big screen, as opposed to doing just like a one-hour Behind the Music kind of doc that they used to do on VH1. So always how layered is the story.

Yes, that is important.

John Scheinfeld: Then I'm also looking at, do we have the audio-visual assets with which to tell this story? Blood, Sweat and Tears was much more of a challenge, as we discussed, because the film and sound had disappeared. But Harry had a life that was very well documented by himself, by his family, by the label. The only thing we didn't really have with Harry was he rarely did TV. He did two programs, and a guest appearance. We had that footage to work with. So the challenge there was how to bring his life to life without having a lot of clips to us.

Right…

John Scheinfeld: Coltrane [was] very similar, in that he never did any TV interviews. Only did a handful of radio interviews and the sound was not good enough to use. But I wanted him to have a presence in the film. Happily, he had done a lot of print interviews over the years with magazines and newspapers. So I took his words from those interviews, and I peppered them throughout the film. Not narration but helping move the story along or giving us an insider's look at what he might have been thinking or feeling at a particular time. Then I decided I wanted a movie star to read those words. Long story short, we got Denzel Washington to speak the words of Coltrane. That was fun.

I can imagine.

John Scheinfeld: Easiest one in this regard, was The US vs. John Lennon. John and Yoko were packrats. They saved everything. Yoko has this wonderful archive on the lower west side of New York. Once I proved myself, they allowed me to go into that archive. We were able to get access to a lot of material which did show up in the final film. That's generally what it is. I think I'm really attracted to the story, but it's got to be also a story about an artist for whom I have some passion. If you're going to spend a year, a year and a half making a documentary, you better love your subject, or I don't think the work is going to be as good.

Blood, Sweat and Tears have had a lot of changes over the years. I mean, even before their heyday, there was the Al Kooper period. Over the years since then, they've had lots of players come and go. In fact, they're still going today. Bobby is still involved, although he doesn't play. Do you think that the film will help new generations to discover the group and perhaps remind the older fans what the group is all about and what was so good about them?

John Scheinfeld: I absolutely hope so. In this film, you see just how great this band was. [People don’t] know all these albums. After the self-titled album, there was BS&T 3, BS&T 4. That's really when the band began to fracture. At the end of ‘71, David Clayton-Thomas and two other guys left. In 1973 another three guys left. Bobby soldiered on for a few years and then he left. And then no more albums. David continued on with the band. It was David Clayton Thomas and Blood, Sweat and Tears or some version of that. They toured all over until about 2004, when he stepped back.

Bobby Colomby: I honestly hope so. I have no financial interest in [the film]. But I hope it gets a lot of exposure, because I think people will go “they were good.” That type of music inspires musicians. Not mechanical stuff. Not like computer generated stuff. Then you just want to do the same thing on your computer. It doesn't necessarily make you want to play an instrument. It doesn't sound dated to me. Well, then again, you're asking me, it's the wrong guy. (laughs)

John Scheinfeld: Ever since there has been a traveling version of Blood, Sweat, and Tears. They play small performing arts centers, and clubs, and casino theaters, and those sorts of things. Bobby is fond of saying that they're better than that original band. Can't really speak to that, but they're very good. So good that for the dramatic, original score of this film… those are the moments where we're telling the story, but Blood, Sweat and Tears isn't performing or we’re not using an album track. It's just music to give you the flavor and the texture of a particular dramatic moment, whether it's a drama, thriller, poignant, scary, whimsical, whatever the flavor is. I persuaded Bobby to co-write that original score and we had it performed by the current Blood, Sweat and Tears band. So it kind of comes full circle here.

Yes, it does.

John Scheinfeld: But as you rightly mentioned, after 1973, there was a there were a lot of musicians – like 170-some – that have come through the ranks of Blood, Sweat, and Tears. Our story is very much confined to the second iteration of the band, the nine guys that had the self-titled [album] and then BS&T 3 and 4. We don't really concern ourselves with what happened before or after. Because we're really doing a moment in time, not a history of the band.

Not only were you a subject and a participant in the film, but you also scored the movie. I don't think you've ever done that before. How did that come about? What was that like?

Bobby Colomby: That's strange. John is a persistent little bugger. He was on my case. He said, “I want you to score it.” I produce music. I can arrange music. And I can write [songs]. But I don't notate physically. I can’t read or write music. I'm illiterate in that department. I know the instrumentation. I can describe the sound I'm looking for. I can sing melodies. I could sing the notes of the chord I'm looking for, but I can’t play it. Throughout my career as a producer, I've always had someone in the room that I relate to, that I can talk with and say, “In this section, here's I'm looking for. Something that does this or something that does that.” So I just said, “I can't do it, John. There are so many great composers.” (laughs) He was smart because I didn't charge anything. I think that was probably what was behind it all.

John Scheinfeld: When I do a film about an iconic musician, I try to have only that musician’s music in the film. For US vs. John Lennon, it was only John Lennon songs. Even in the dramatic portions, we stripped his voice off and we used the backing tracks. It was all his music. Same with Harry. Same with Coltrane, although, no vocals, so we had a great wide range of music. In this one we did have all these dramatic moments. I just felt I wanted it all to be Blood, Sweat and Tears music or in the style of. Who better to compose that music than the co-founder of the band and the guy who became the leader of the band?

Bobby Colomby: He was saying, “Look, you're the guy that came up with the concept of this band. I want that same kind of musicality for the score.” I tried to get out over and over.

John Scheinfeld: He was like, “No, I don't want to do that.” Bobby come on, you got to do it. “Nah…”

Bobby Colomby: Finally I just said, “I have a friend that I've been working with. He can read me really well.” I would sit with him. There's a thing you do in the film biz… (laughs) like I have any clue what that is all about. It's called spotting. That is, when you sit with a director and you're a composer, he shows you the moments in the film when he wants music. He'll say, “Listen, right here, the bad guy gets killed, but don't hint. Don’t do that, but I need this.” They guide you to some degree.

John Scheinfeld: He finally agreed to do it. Then for like the next three weeks, he was trying to get out of it. “Maybe you need to find somebody else.” I think as he says about me, I was just a pain in the ass and persuaded him to do it.

Bobby Colomby: John just showed me where he wanted the music. The beginning, or the invasion of the Russians into Czechoslovakia. I'm a [Sergei] Prokofiev fan. He's my favorite of all the classical composers. He's a very modern composer. I would sit with my friend, Dave Mann, who is a wonderful sax player, but he's great with synthesizers. He's great with Pro Tools and all that stuff. I just said, “Okay, here's what I need. I need this like Prokofiev kind of. Bassoon, I want an oboe against it. I want this melody. I would go through it. He’d take it to a much higher level than I could imagine. He was great. I give him way more credit than I would take for it. If someone called me, “Hey, you did that? Would you want to do my film?” I'd say let me find out if Dave's available.

John Scheinfeld: Your readers will discover just what a great score it is when they come to see the film.

Bobby Colomby: Actually, it turned out to be a tremendous amount of fun. The real kicker of this is I use the current day version of Blood, Sweat and Tears to play on it. They're so much better than we were. (laughs) It’s actually funny. When we were in the studio, there were some guys in the band that weren't wonderful and some guys that were fabulous. The not so wonderful guys brought down the fabulous guys in the recording because it wasn't all digital back then. You actually had to play it. It wasn't cut and paste. You had to go for it. It took a minute. These guys go in and thank you, that was take one and that's all we need. Let's do that. Now let's go to this section. Okay, thank you. That was take one, that's all we need. They were fantastic. The drummer is like 1,000 times better than I ever was.

Just as a fan, what are some of Blood, Sweat and Tears’ greatest moments musically as far as you're concerned?

John Scheinfeld: For me? Well, it's interesting as the film has gotten out in theaters, and we've gotten a lot of great press on it, what we find in the questions – whether it's from media, or from people at the Q&A's – is that there are some people out there who are Blood, Sweat and Tears fans, but they're really devout Al Kooper Blood, Sweat and Tears fans. That first album Child is Father to the Man. Or they love the self-titled and the other albums because they think David Clayton-Thomas is one of the great voices of rock'n'roll of that era.

That is true.

John Scheinfeld: I don't think I have to choose. I like both of them. I love that first album. I love the self-titled album. I think “I Can't Quit Her” and “I Love You More Than You'll Ever Know” from the first album are just terrific. I love their rendition of Harry Nilsson's “Without Her,” it’s bossa nova and it's terrific. I don't think there's a bad song and the self-titled. I can listen to that start to finish anytime and be totally enthralled by it. 3 and 4 are a little different. Love “Hi-De-Ho,” great song. “Lucretia McEvil,” great song. “Go Down Gamblin’,” great song.

It was.

John Scheinfeld: I think when we talk about What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat and Tears is coming back from this tour and what they encountered and found themselves embroiled in exacerbated personality conflicts that were in the band. Sometimes in a group that stuff gets papered over when success is there, but when more difficult times come, it really emphasizes that some wanted to play more jazz and some wanted to play more rock. Some didn't like this song. Some didn't like that song. You end up compromising. I think we see that in some of the later albums where the material is not as strong as that self-titled album. People begin to think, as Bobby says, that this band is in trouble, and I got to start thinking about what my future is going to be. That's when I talk about the moment was not the same, I think not only personally, but musically. I don't think they ever equaled that second set, self-titled album.

I agree, although I like you said, I do agree that there were some really great songs on the later albums.

John Scheinfeld: I will say I never really liked Jerry Fisher, the singer they replaced David with. There were a couple of nice songs. “Down In the Flood” is a nice song. “Roller Coaster” is a nice song. I did think when David came back to the band in ‘75, and they put out this album, New City, I thought that was a pretty good album, pretty strong. The problem was that the musical tastes in the world had changed by then. Disco was coming in. I think the moment had passed for this kind of horn-based rock.

I was surprised when I was looking into this to find out – which I shouldn't be because there are lots of bands that should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame that aren't – but Blood, Sweat and Tears is not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Do you think that hopefully maybe getting the word out about them for that might rectify that overlook as well?

John Scheinfeld: I hope so. I think it's a well-deserved honor. Some of the people that they're taking into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now aren't even rock and roll. I'm not quite sure why they're there.

Bobby Colomby: It's not surprising to me. Because there were gatekeepers, like the Jann Wenners and the Jon Landaus. They never played a note, really. I've never been inspired by anything they've done. Telling me you're not good enough. You haven't affected music. You're not cool enough. That's a badge of honor at this point.

I think that Blood, Sweat and Tears was plenty cool.

John Scheinfeld: Here you have a band that had a really innovative approach to rock and roll by incorporating the horns and the rock and the jazz elements. They were so innovative. They influenced many horn bands that followed, or bands that incorporated horns that followed. I think that's very worthy of being in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

When is the movie going to be opening nationwide? Or is it spreading from town to town?

John Scheinfeld: We are nationwide at the moment. We opened in New York on the 24th of March we opened in LA and the 31st. Then we've been going wider. We're now in over 80 theaters in 40 markets across the country. That number is growing every day. It's one of these things where theater owners see how it's doing in other theaters, or they see the great press or hear podcasts like yours. They are like, “Oh, we got to look into that.” And then the “Oh, that's good.” So they've been adding us, which is really, really great. For your readers, if they go to our film website, which is BSTdoc.com and in the upper right hand corner, they click on watch, every theater showing us is listed there.

I'm in Philadelphia, so I'm sure that if it hasn't come here yet, which I don't believe it has, I'm sure it will be sometime soon.

John Scheinfeld: Yes, I think so. Then, as you mentioned before, we have a soundtrack coming out in two parts. On CD and digitally are all of the live tracks that appear in our film that were recorded during the Iron Curtain tour. Those are the ones that Bobby and Alan Sides mixed. They're fantastic. They're just great. Then the original score that Bobby did with David Mann, a great musician, will be available digitally. That's Omnivore Recordings. You can either find information about that on the film website or on the Omnivore website.

Copyright ©2023 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved. Posted: April 18, 2023.

Photos #1 & 2 © 2023 Jay S. Jacobs/PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Photos # 3 – 8 © 1969-2023. Courtesy of Abramorama. All rights reserved.

Comments