Michael Joseph Gross

Stars in Our Eyes

by Ronald Sklar

We’re surrounded by them from birth to death. They are as much a part of our lives as our family, friends and children. They give us love, shape our worldview and influence the way we see ourselves; they give us sexual satisfaction; they disappoint us and sometimes leave us. We often keep our love for them a deep, dark, shameful secret – for others, we proudly announce our love for them to the world.

They are celebrities.

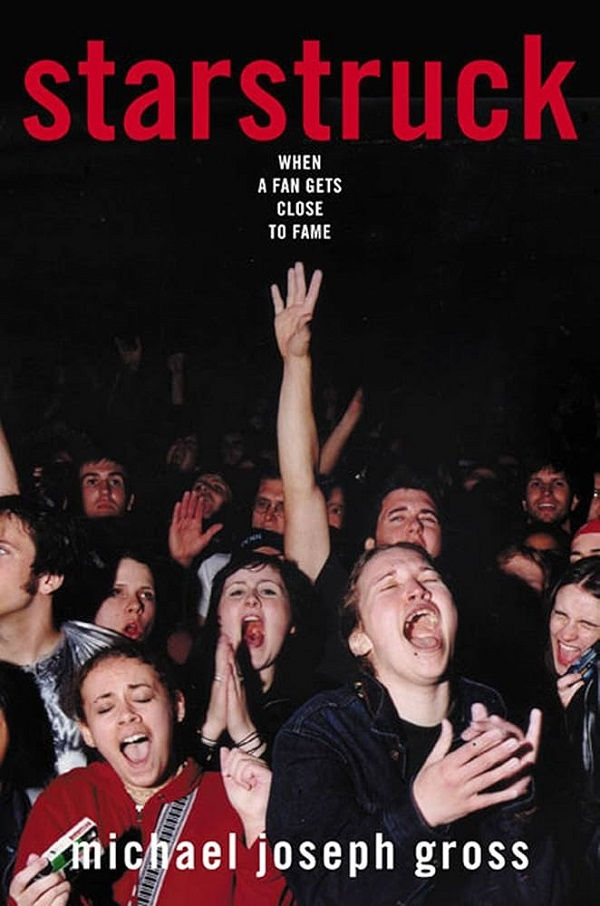

In Michael Joseph Gross’ excellent, mesmerizing new book, Starstruck (Bloomsbury USA), the strange but common relationship between fan and star is examined and dissected. Most of the experience is related to us firsthand, as Gross moved to LA to be closer to the action. He also spent his Midwestern childhood obsessively collecting autographs.

He explores why we are so drawn to famous people and how they react to us. He also investigates why our obsession with celebrity is stronger than ever, and yet very few of us would ever admit out loud that we are vulnerable enough to fall for it.

What exactly is the strange phenomenon of celebrity and how and why do we become fans? It’s a subject that is rarely dealt with, and the book is an eye-opener.

Michael Joseph Gross is a freelance writer who has written for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic Monthly, Entertainment Weekly, Elle, The Nation, and many other magazines and newspapers. He won PEN/New England’s 2002 Discovery Award for nonfiction.

It’s obvious that you’ve poured so much of yourself into this book.

I decided that the only way to write this book is as if I had nothing to lose. There are so many truths that entertainment journalists shade, truths that we only allow partial expression. If you are going to write something that means anything, you have no choice but to do your best to tell the whole truth. It also makes things funnier. At some point during my writing of this, I found a quote from Mark Twain that said, ‘The absolute truth is the funniest joke in the world.’

What inspired you to write this book?

After college, I went to seminary. After seminary, I worked in politics as a speechwriter for the governor of Massachusetts. After that, I became a freelance writer and I found that most of my articles were about admiration, how admiring someone helps form character.

For me, because autograph collecting and being a fan as a kid were such important ways of making myself up, I decided to look at the paths other people have taken in fandom too.

The first expedition I took was to write a piece for The New York Times magazine, about professional autograph collectors. That story – to my surprise – really hit a chord with a lot of different kinds of people, including very powerful media people who you wouldn’t expect to identify with passionate fans. But they do. Few people working in the media or entertainment ever make anything meaningful that is not fueled in some way by the emotional impulses of fandom.

I thought that it might be worthwhile to go to LA and find out how fandom expresses itself up and down the social spectrum, in obvious people like autograph collectors, but also people who you wouldn’t initially think of as fans but who are – celebrities, directors, producers, writers.

You’ve said that our culture encourages us to become fans, but when we do, we are labeled as freaks.

The same media that force feeds us images of celebrities also tells us that fans are freaks. We’re in a huge hurry to trivialize fandom – to call it shallow, empty, corrupting, juvenile.

How do you see the difference between fans and stalkers?

Stalking is a symptom of severe mental illness. It has nothing to do with the everyday insanities of fandom that the rest of us experience. Stalking is not the funhouse mirror image of autograph collecting. It is a whole other territory. And yet, there is something really intellectually appealing to a lot of people about the idea that the fan is a stalker waiting to happen. It makes a tidy argument.

How has the internet changed fandom?

One of the effects of the internet is to create the illusion of greater intimacy while actually increasing the distance between stars and fans. The internet allows greater bandwidth of information about stars’ personal lives but actually lacks personal involvement in the purveying of that information.

Increasingly, you’re also seeing stars create websites that have two levels of access, just like porn sites. There is one level that you get for free (example: Halle Berry’s site: Hallewood.com) where you can look at QuickTime movies of Halle working out, running on a treadmill, doing her abs routine. This level is for free. Then you have a chance to enter a sweepstakes to see her in person, or even have a chance to ask her a question that she may answer on the website. This level is something like thirty-nine dollars a year. For that, you also get a fake autographed picture.

A lot of celebrities have this same model. It’s mostly female stars who are in some way sex symbols. There aren’t as many male stars who have exploited the medium yet. But one great one is Adam Sandler’s website which is filled with amazing short movies. Adam taking care of his dying dog or getting a haircut. We see every little detail of his life. That is an example of a site that offers greater intimacy and actually does deliver it. In no way does it profit from the interactions that it invites.

That is what I think is most telling about the majority of movie stars’ websites. Any of us born in 1970 or earlier could make contact with a star by just writing a fan letter and putting a stamp on an envelope. It’s almost impossible to do that now. Through the Internet, stars have learned that they can ask for—and get—a considerable amount of money, just for providing the illusion of personal contact.

You show us two extremes in perceptions of star power: Michael Jackson and Dolly Parton. In many ways, both stars are very similar, but how do they differ?

Even though they are two of the most spectacularly artificial human beings living in America, Dolly has been able to convince the world that she is real. That’s the word everybody uses to describe her: “She’s just so real.” She evokes both the kind of awe we reserve for stars from outer space (Michael Jackson, Cher) and at the same time the fellow-feeling that we have for stars who are most like us (Tom Hanks, Meg Ryan). She is a true paradox. Nobody is more artificial, and nobody is more authentic. Paradoxical characters I think are the ones who are of the most enduring interest. Jesus fascinates because he is a paradox.

Michael’s story is an American Tragedy. And Dolly is the classic American success story, the American Dream. Jackson’s story is like a warning: if you start transforming yourself, you might not know when to stop. You just lose yourself completely. However, Parton’s life is like a promise, that if you start transforming yourself, you become more essentially yourself. She has had all this plastic surgery, but she is almost like an artist of plastic surgery. The more she changes in order to fit the vision of herself that she had when she was a kid, the more people love her.

You also touch upon the state of entertainment journalism and how it influences fandom. You use Mary Hart as a prime example of how the industry has changed over the last few decades.

Writing about entertainment journalism, I chose to concentrate on Mary Hart because I think that Entertainment Tonight (ET) is the watershed event in the history of entertainment journalism and has not been sufficiently recognized as such.

ET was the first syndicated show to be sent by satellite to stations around the country. Mary Hart was not just on-camera talent, but she was traveling all over the country to build this business and sell this show in a way for which she has never been given credit. She is an extremely smart businesswoman. Her longevity alone as a woman in this business is just staggering – she’s weathered five co-hosts in twenty-some years.

ET took real information about the business of the entertainment industry into people’s living rooms for the first time. This show was the first to report things like box office grosses. Before this show, none of us talked about that.

Over time, however, ET became more sensational, more preoccupied with gossip. Its notion of entertainment broadened to include stories like the Michael Skakel trial and Chandra Levy’s disappearance. More and more competitors arose (E!, Access Hollywood, etc.). ET has gone way off on the side of gossip. This has probably been difficult for Mary Hart.

The evolution of entertainment journalism over the past couple of decades reflects the evolution of entertainment in America. Particularly in the last five years, looking at the rise of reality television, this is where things have gone completely off the rail.

Entertainment and gossip have completely merged. Reality shows are interesting because they’re filled with people who do the kind of things on camera that until recently none of us would even admit to our friends that we did: lie, cheat on our spouses, say horrible things to our parents.

However, I think that we may be due for a change in course here soon. The biggest new TV shows of the last season were Desperate Housewives and Lost. And the recent announcements of the new shows on the networks’ fall schedules indicate that we are moving back in the direction of the primacy of scripted entertainment. That’s because fans have an appetite for story and characters and not merely for sensation—and that appetite for narrative is by far the more sustaining pleasure.

How have publicists’ roles changed in the last few decades, and how are they associated with fandom?

Publicists have more control over access to the stars now. They’re strange characters, publicists. Most of them have a lot of disdain for fans, and I don’t think it’s hard to figure out why that is. How can you ever turn your life so over wholly to the creation of a star and to serving the whims of a star as a publicist does, unless you are dying to breathe the air of fame?

You describe “People Storms” in your book when you discuss your red-carpet experiences with Sean Astin.

One of the reasons I love talking to Sean Astin is because he is able to describe the experience of fame from so many different angles. He grew up as Patty Duke and John Astin’s son, and he was a child star himself.

He is now an adult and has children of his own. He is observing the way his career affects their lives. One of his daughters becomes very frightened when they go out in public, and people start to ask for his attention. She calls what happens a “people storm.”

Sean allowed me to accompany him down the red carpet as he entered an awards show. The fans in the bleachers think that the celebrities see them as a sort of anonymous mass, when in fact, the entire time we were walking down the red carpet, Sean was noticing very specific things about individuals, and talking about why they were dressed the way they were dressed or why they were saying the things they were saying. You would hear these large, loud obtuse comments like “You’re great!” coming from the stands. But we were surrounded on the red carpet by people like Dennis Quaid and Uma Thurman and Queen Latifah and I would listen to what they were saying to one another, and it was essentially the same thing, often the same words: “You’re great! You’re great!”

At one point, Sean put his arms around my shoulder and, gesturing to the fans, said, “Aren’t you glad that you’re over here instead of over there?” It sounded almost like he was bragging, which would have been out of character for him. I was wondering what he was getting at, and I said, “Yes, I sure am.” He asked me, “Do you know what the difference is? About two feet.”

How do you feel about celebrities now that you’ve exorcised your thoughts in this book? Are you completely over it?

I am on sabbatical! However, if I walked out the door and Renee Zellweger was walking down the street, it would make me very happy for about five minutes. But most of the time, when an opportunity arises to go to a celebrity party, I’d rather go to the beach.

So what is it about our love affairs with celebrities? Why are we all fans?

Celebrity is something that we enjoy, even if we don’t admit that we enjoy it. And for the most part, it’s good to enjoy it. It’s healthy. It helps connect us to other people: we really can learn something about a new friend by asking, ‘Who’s your favorite Desperate Housewife?’ Also, if we didn’t have these people to dream about, then we would have to do some serious hating of the unfairness of life. And our relationships with stars ebb and flow, just like all of our relationships. We need them more and less at different times of our lives, and we need different kinds of them at different times of our lives.

It’s like love, but it’s not love, and it’s really important never to forget that. This is an imaginary relationship. The connection that we feel to a star is actually a connection to a piece of work that the star has made. This adds a layer of abstraction into the relationship and makes it less like love, and more like being in love with love.

The initial impulse of fandom always comes from the impulse to love, and that’s why fandom matters. That’s why none of these feelings -- no matter how stupid and silly and embarrassing they are -- none of them are a waste of time or shameful. They are just there to enjoy. Celebrities give us pleasure that almost no one has bothered to describe.

Copyright ©2005 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved. Posted: June 5, 2005.

Photo Credits:

#1 © 2005 Dante DiLorita. Courtesy of Bloomsbury USA. All rights reserved.

#2 © 2005 Courtesy of Bloomsbury USA. All rights reserved.

Comentarios